The next question that evening was which building technique to use. Einstein wanted a log house, the oldest and most traditional type of wooden home. It´s solid timber construction the walls consist of full stacked logs that dovetail at the corners convey a sense of heavy permanence not unlike that of stone. Yet Wachsmann had reservations. Having designed a log house the previous year for a director at Christoph & Unmack, Wachsmann knew firsthand that they required large quantities of seasoned wood, highly-skilled carpenters, and experienced planning. The tendency of the logs to dry and shrink in the first two years meant that clearance had to be carefully calculated to avoid burst pipes and out of kilter windows and doors.

Wachsmann proposed two alternatives. The panel system was based on a technique invented by a Scandinavian military officer in the late nineteenth century for building temporary wooden barracks. It consisted of stackable and transportable wood panels that could be connected with one another via metal catches the architectural equivalent of Ikea furniture. After Christoph & Unmack acquired the patent rights in 1882, the system was further expanded to include modular panels for windows, wall, roofs, and floors.

Yet because the Einsteins wanted a house with French windows that at least resembled a log house (both impractical with the panel system), Wachsmann recommended a second option: the balloon frame system. Developed in Chicago in 1830, the balloon frame system was a modern version of the half-timber construction popular in Northern Europe since the fourteenth century. The main difference was the frames reliance on light studs joined by machine-made nails instead of heavy timbers joined by mortises, tenons, and wooden pegs. The system, which was already well established in America, had everything that post-war German builders were looking for: it lent itself to industrial standardization yet could be easily modified to meet individual tastes; it could be erected quickly by unskilled workers yet incorporate principles of modern design; it was inexpensive yet durable.

Einstein was impressed with Wachsmann´s knowledge and agreed with his recommendations but was non-committal about the project. The mayor attempts thus far had made Einstein chary. He did, however, ask Wachsmann to assume further negotiations with the city, as he was tired of playing the role of real estate broker. Much later Wachsmann would express his amazement at how so much trust could develop so quickly between two individuals who until that afternoon had been complete strangers.

In the following weeks, the city presented over a dozen properties. Whether because of access (one property could only be reached by passing through a neighbor´s barn), noise, small size, poor location, or bug infestation, Wachsmann rejected them all. During the unsuccessful search for a plot, more bad news came. Böss informed the Einsteins that the city could only purchase the land for the house; the Einsteins would have to finance the house themselves. Because the offers were so unsuitable, Wachsmann suggested to the city that the Einsteins find the property; the city could then provide reimbursement for the costs.

In the meantime, Wachsmann had prepared new plans. They represented the dream house of a young architect who took his cue from postwar German architecture: flat roofs, large open windows, smooth lines. When Einstein saw them, his response was unenthusiastic. He wanted a home, a place for security and comfort, not an art exhibition that „looked like a cardboard box with giant showroom windows.“ It wasn´t just aesthetics. Einstein wondered whether Wachsmann´s flat roofs even had a practical function. If they did, then why didn´t past builders use them? „Could you imagine a cathedral with a flat roof?“

However, Einstein could think of something certainly practical in design: sailing boats – prompting him to invite Wachsmann to go sailing with him. And indeed two weeks later, Wachsmann arrived at Caputh, where Einstein had friends and access to a sailboat. Although Wachsmann had dropped off revised plans the day before in Berlin, they didn´t talk about the house. It wasn´t until they returned to shore that Einstein mentioned with great discomfort that he had sent a letter to Böss declining the cities present. Wachsmann was devastated. Without the cities support, the Einsteins weren´t going to build. To console himself, he took a long weekend in Paris, where as a student he had gone to meet Le Corbusier and study modern architecture.

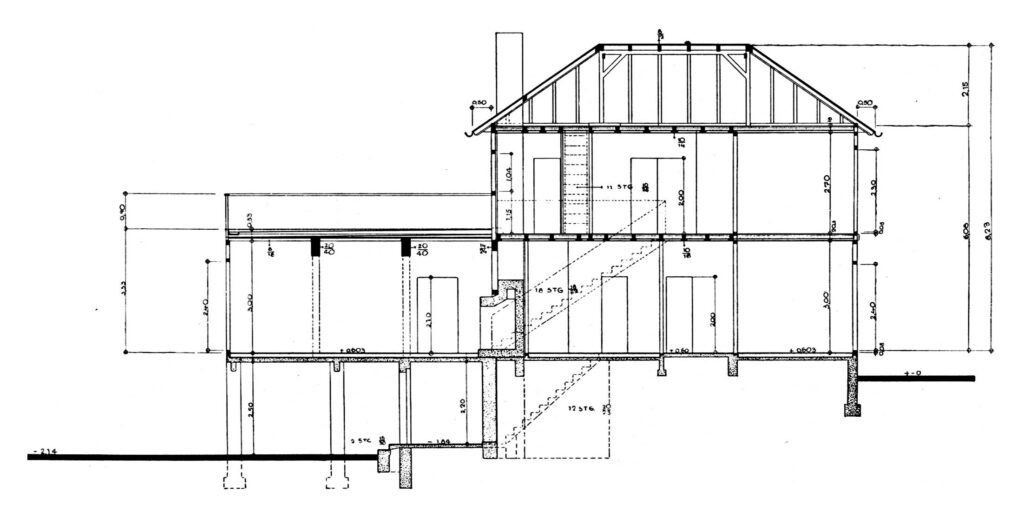

While Wachsmann was in Paris, Einstein had a chance to look at the revised plans. They revealed the work of two minds. One part clearly conformed to what the Einsteins wanted: a wooden two-storey house with a tile roof. To give the impression of a log home, Wachsmann let the heads of the base beams between the floors extend beyond the cladding. (This purely cosmetic feature has served its purpose well. Visitors and historians alike often mistake the house for a solid log construction.) The other part of the house, joined perpendicularly to the former, was a flat-roofed cube construction very much reminiscent of the modernist style represented in Wachsmann´s second draft. French doors replaced the showroom window and the supposedly non-functional flat-roof was given the function of supporting a large open terrace. After studying the plans for a few hours, Einstein asked Elsa how much money they had in the bank. When she asked why, he said: „I would like to have this house, and I will probably have to pay for it myself!“

Now the Einsteins had the house; what they needed was the land. Help came when friends of the Einsteins who had heard about their search called to offer them a part of their property in Caputh. It was not directly on the water, but it was more promising than the others offered by the city. Situated on top of an incline and abutting a state forest, the property looked out over Lake Templin and was only a ten-minute walk from the boat launch. Wachsmann approved, but suggested that the Einsteins buy an 11×23 m swath of land along the forest path that belonged to the Prussian state. This would give the property better access, and, because it was higher in elevation, better views. The same day that Einstein saw the property he decided to take it.

Yet finding the land did not solve all of the Einstein´s problems. Though Böss renewed his offer to purchase the land, it turned out that he had no legal authority to do so. A proposal first had to be passed freeing 20,000 marks for special land acquisition. Now, instead of being a discretionary decision made by the Social Democrat Böss, the matter had to go before the entire city parliament. Predictably, the proposal encountered resistance. It was a generous and unprecedented civic gift, and it was being given to a Jew in an increasing anti-Semitic atmosphere. German nationalists in the city parliament dragged their feet and insisted on a closed-session debate. By May 14th, Berlin papers were reporting that Einstein had sent a letter to Böss formally declining the gift once again. „Life is much too short, and the affair concerning my honorary present has lasted much too long, for me now to be able to accept it,“ Einstein wrote. Böss tried to convince Einstein to reconsider, but whether because of fear of arousing further anti-Semitic sentiment, because of pride, or because an avowed socialist was uneasy about accepting a gift of land from the state Einstein declined. He would build the house without the cities help, even if, he told Wachsmann, he had to starve.

On May 12th, Einstein countersigned the blueprints, officially closing with Christoph & Unmack. The same day Wachsmann applied for a building permit in Caputh and by the middle of June it was approved. By that time, the plans had been somewhat modified to better suit the site. Wachsmann took advantage of the properties incline and made part of the basement into a covered garden terrace to provide shade on hot days. He also moved a window in Einstein´s room from the south wall to the west wall, so that Einstein would have a view of the lake.

While the foundation of the house was being laid in July, workers at Christoph & Unmack were erecting the houses skeleton in one of the firmas large industrial halls. Once engineers had confirmed the fit, the skeleton was disassembled and the supplies were packed and sent to Berlin. At the site, workers needed only two weeks for framing and cladding, another two weeks to finish the interior, and by September the house was ready. Four weeks later Einstein wrote to his sister, I like living in the new little wooden house enormously. Even though I am broke as a result. The sailing boat, the distant view, the solitary fall walks, the relative quiet, it is a paradise.“