The Interior

Following a series of twists and turns after he completed the Einstein house freelance work in Berlin, stays in Rome and Paris, emigration to America, and a failed joint-venture for prefabricated building components with Walter Gropius Konrad Wachsmann established himself in the world of architecture. He invented an ingenious system for constructing large aircraft hangars, designed civic buildings, and taught at the Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology and the University of Southern California. Of his achievements, Einstein´s house in Caputh was neither the most important nor the most interesting. But at the end of his life Wachsmann said it was his favorite.

Although Wachsmann never worked at the Bauhaus, and often distanced himself from it as an institution, he followed the basic principle of the Bauhaus founder, Walter Gropius, of combining art and technology, the individual and the industrial. This philosophy contained socialist aspirations that Einstein certainly would have embraced, even if he was less than enthusiastic about modern architecture. Instead of catering exclusively to the wealthy elite, Bauhaus designers wanted to use mass manufacture to produce affordable, functional, and aesthetically pleasing objects for everyone.

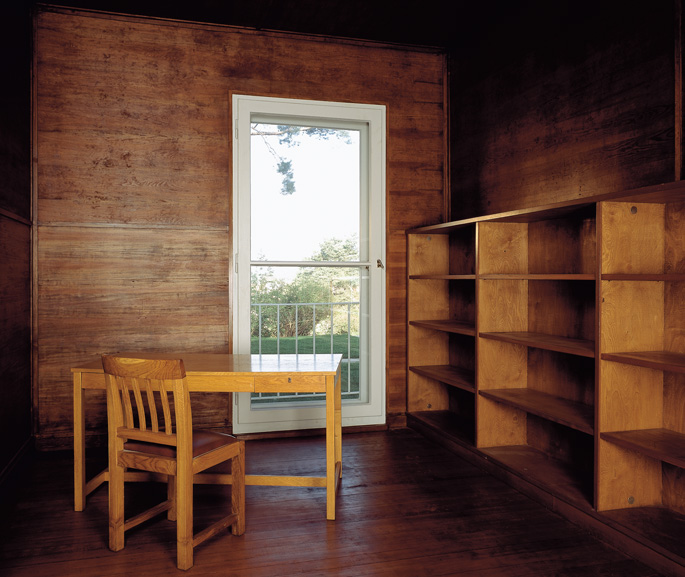

The interior of the house is spectacular for its combination of function and beauty. Except for the bathrooms and the kitchen, the walls of the downstairs rooms and staircase are cladded with pine. A clear gaze brings out the gorgeous natural color of the wood and provides the warmth and comfort that Einstein wanted in a home. The spacious living room is outfitted entirely in solid wood panels. Two massive beams of Oregon pine, each nine meters in length, extend from the rear of the living room through the exterior wall, where they support part of the rooftop terrace. For someone standing in the living room looking out the large French doors, the beams provide a theater-like projection of perspective, with the view of Lake Templin in the distance serving as the natural focus.

Although the house is by no means large, Wachsmann´s imaginative use of space lets the house appear roomy. Each bedroom contains a built-in bed niche that maximizes living area. Even the three tiny upstairs rooms, none larger than 11 m2 (100 ft2), have closets and washing stands without seeming cramped. Contributing to this effect are the interior doors, which, when closed, lie perfectly flush with the wood cladding of the walls. Another particularly clever use of space is the pass-through between the living room and the kitchen. Dishes and tableware can be prepared unobtrusively in the adjoining kitchen, placed in the wooden hatches, and collected in the living room on the other side

In addition to the interior appointments, the Einsteins asked Wachsmann to supply the house with furniture. Wachsmann didn´t have time to do the work himself, so he approached Marcel Breuer, a young up-and-coming Bauhaus designer from Dessau whose 1925 chair for Wassily Kandinski had become an iconic Baushaus form. Wachsmann thought that the clear and simple lines of Breuer´s designs would resonate with the interior of the house and appeal to the Einsteins. Yet Breuer´s designs were no better received than Wachsmann´s second draft of the house. Einstein was just as inclined to sit on furniture that reminded him of a machine shop or a hospital operating room as he was to live in a house that reminded him of a cardboard box with showroom windows.

In the end, the Einsteins were not concerned whether their interior design harmonized with the rest of the house. The only truly modern fixtures for the interior were the round Bauhaus lights that hung in the rooms and hallways. It has been argued that the Einsteins rejection of the Avant-garde was an expression of middle-class taste, but in this case they were probably more pragmatic than conservative. Their bank account almost empty, they decided to use furniture they no longer needed in Berlin. The only piece specifically designed for the house was Einstein´s desk, and the instructions Einstein gave Wachsmann were Bauhaus-like in their simplicity: the desk was to be neither too big nor too small; it had to be large enough to hold a lamp, a box with blank paper, and box for his notes; and it was to have exactly three drawers. The desk, along with the rest of the furniture, was lost sometime after 1933.